New Leadership True Democracy in Action.

December 2, 2013

JOGISHWAR SINGH

As a Swiss citizen born in India, I am many times brought to think about my experiences of the democratic systems prevalent in the two countries.

Before Indian ‘patriots’ start screaming murder at what I am going to say, I should point out that I am fully aware that I am talking about two different historical realities.

Switzerland has been independent for over 800 years while India is a newly created entity, now a mere 66 years old.

Switzerland has a population of only 8 million while India has the second highest population of any country in the world at over 1.2 billion (give or take a few million). And expected, in the near future, to even outstrip China, and become the world’s most populous.

The trigger for this set of reflections was what I saw on the 7.30 pm evening news on Swiss TV a couple of weeks ago.

The Swiss President, Mr Ueli Maurer, was leaving on a five day state visit to China. The news showed him arriving at Zürich airport in an ordinary private vehicle. The President got out of the car by opening the car door himself. He walked to the nearby baggage trolley stand outside the airport entrance. He took a baggage trolley out, rolled it towards the car, lifted his suitcase and travel bag himself, put these on the trolley which he then rolled towards the entrance like any passenger lambda like you or me. He walked up to the check in counter with just two other persons walking behind him. He checked his luggage in for a commercial flight without any special treatment being meted out to him.

For any Indians (or others) who might find it difficult to believe what I have described above, you can CLICK on the link provided hereunder, at the end of this article, to view a TV news clip from the evening prime time news for July 16, 2013..

You’ll get visual proof of the Swiss President’s arrival at the airport, his check in for his state visit to China and a short interview with a TV journalist. This clip is really worth watching.

Conditioned by my personal experiences of dealing with politicians and government ministers in India while serving as an IAS (Indian Administrative Service) officer, I was so struck by the contrast between what I had experienced in India and what I was seeing on the TV screen that I told my wife that this represented one of the finest examples of democracy for me, certainly of the Swiss variety. It made me proud to be the citizen of a country where the serving President behaves like an ordinary citizen and does not feel the need to consider special privileged treatment as his divine birthright.

I remembered the countless times when I had seen the fury of Indian politicians, much below the level of the President of a country, at what they considered as a slight because they had not been treated as demi-gods.

I am not a psychologist. I do not know whether centuries of slavery have generated this distorted VIP culture in India but I remember that we all did curse the politicians there for causing so much inconvenience to the general public by expecting, demanding and getting privileged treatment.

Who in India, except maybe some politicians or bureaucrats, has not been inconvenienced by VIP visits for which miles of roads and highways, even entire neighbourhoods, are blocked off to traffic, and flights are delayed, awaiting the arrival of some VIP or even his/her flunkies/family members?

Any such inconvenience would cause an uproar in Switzerland.

In India, it does not generate even a whimper.

In this context, an incident from the not very distant past strongly lingers in my memory. A few years ago, a former IAS batch-mate of mine (1976 batch) had visited Switzerland.

I have noticed that Switzerland becomes a prize destination of choice for a lot of Indian ministers and bureaucrats during their hot summer for attending all kinds of useless conferences which are essentially talking shops organised by the United Nations, an organisation which is a hotbed of nepotism and inefficiency.

This IAS officer wanted to see Switzerland, so I acted as his local tourist guide.

While we were going around the Swiss federal capital, Bern, it was lunch time so we decided to have lunch at a restaurant very close to the Swiss parliament building.

As we took our seats at a table, a Swiss gentleman sitting at the next table, reading his newspaper while sipping his coffee, greeted us in English. While we ordered our meal and waited, he finished reading his newspaper, drank his coffee and called for his bill which he paid before leaving. While going out, he again politely wished us goodbye, even saying, “I hope you enjoy your stay in Switzerland” in English.

After he had left, I asked my visitor if he knew who the man had been. Obviously, my visitor did not know the answer. I informed him that we had just been greeted by the then serving Swiss President, Mr René Felber.

My guest thought I was making fun of him. He would not believe me so I called the restaurant manager to confirm the veracity of what I had told him. The manager duly confirmed what I had said.

My Indian visitor was flabbergasted. He said, “How can this be possible? He actually paid his bill before leaving”.

So, what struck my visitor the most had been the fact that a VIP had actually paid his bill! I wonder what he would say if he saw our current President, Mr Ueli Maurer, personally loading his bags on to a baggage trolley and wheeling it to a check-in counter just like any ordinary citizen. His disbelief could only be countered by visual evidence on the TV!

My visitor’s reaction brought back memories of when, as a serving sub-divisional or district level official, I had been called upon to organise lunches and dinners for numerous collections of freeloaders travelling with ministers or bureaucrats in India.

I seldom remember any politician or bureaucrat actually paying or even offering to pay for the bonanza laid out for them. Those who did offer to pay, did so at the ridiculously low official daily fare of eleven rupees (today, a mere 20 cents US) per person or something like that.

Nobody ever asked how it had been possible to lay out a lavish meal comprising several dishes, accompanied by expensive alcoholic beverages, for such a petty sum. I never found out myself who used to pay for all this extravaganza at the end of the line.

Like a good Indian bureaucrat, I just used to pass the buck down the line to my junior magistrates and revenue officials. To this day, I am unable to clarify which poor victim — read, citizen! — who got stuck with paying for all the freebies on offer.

While working as chief of staff to the President of the Swiss Commission for the Presence of Switzerland in Foreign Countries many years ago, I had the chance of accompanying him to Strasbourg for meetings of the Council of Europe. I also had the privilege of close interaction with several Swiss members of parliament over an extended period of 12 to 14 months.

The contrast to the behavioural pattern of what I had experienced in India with politicians was so stark that it has stayed seared in my mind even till today.

I am by no means suggesting that Swiss politicians are angels but the kind of behaviour that Indian politicians or bureaucrats get away with as a matter of routine in India would torpedo their careers in Switzerland in a jiffy.

Each such incident deepens my gratitude to Waheguru Almighty for having made me settle down in a country like Switzerland where the President carries his own bags to the check-in counter.

Where no roads are blocked for hours so that some VIP can, in the name of security, be whisked around in convoys of official vehicles.

Where politicians and bureaucrats pay their bills in restaurants.

Where grossly sycophantic behaviour is not the general and accepted norm.

Where no red-light beacons or screaming sirens signal the passage of VIP vehicles. Indeed, the red-light-beacon culture of officialdom in India merits a full story in itself.

I might accept India as a true democracy the day I see its President or Prime Minister behaving like the Swiss President before his departure on an official visit abroad.

I don’t think I will ever see such a sight in India during my lifetime.

You think, maybe, my grandchildren will?

Contributed by Mr. Aditya Khanna _____________________________________________________________________

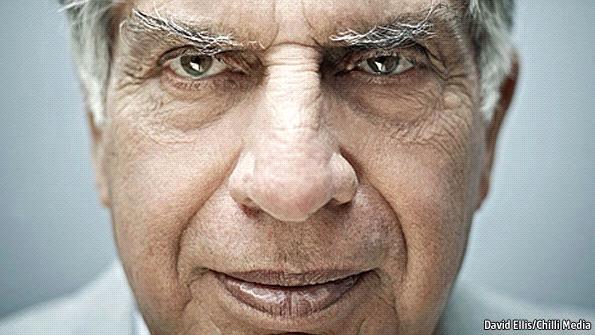

India should learn from the career of its most powerful businessman

IT IS easy to understand why Ratan Tata, who retires as chairman of Tata Sons on December 28th, is important. The conglomerate he runs is India’s largest private-sector concern, accounting for 7% of the stockmarket. It pays 3% of all India’s corporate tax and 5% of all its excise duty. You can live in a house, drive a car, make a phone call, season your food, insure yourself, wear a watch, walk in shoes, cool yourself with air-conditioning and stay in a hotel, all courtesy of Tata firms. Polite, elegant and reserved, Mr Tata has been the king of India’s corporate scene for the past two decades. Indians look up to him in much the same way that Italians once looked up to Gianni Agnelli at Fiat or Americans did to J.P. Morgan.

In some ways, though, the reverence for Mr Tata is odd. He is not a geekish entrepreneur, like the high-tech wizards in Bangalore. He is an old-style dynast—the fifth generation to run his 144-year-old firm. He took time to grow into the job: when he took the reins in 1991 he struggled to assert himself. Even today, critics accuse him of being regal and secretive—and snipe that the group’s most successful business, TCS, its technology arm, is the one he left most alone.

Nor can Tata be hailed as a financial paragon. After a wave of takeovers during the past decade, its return on capital is mediocre. The new boss, Cyrus Mistry, who comes from outside the family (Mr Tata has no children), may have to reorganise something of a ragbag conglomerate: alongside the stars like TCS or Jaguar Land Rover, a luxury carmaker, there is also a long trail of flabby and indebted businesses (see article).

And yet, for all that, Mr Tata’s career carries two powerful lessons for an introverted and corruption-obsessed India. First, that India has far more to gain than lose from the outside world. And second, that a company can be a force for progress.

The hereditary ruler as hero

Globalisation came easily to Mr Tata, who trained as an architect in America. Even today he would rather discuss car designs with young engineers than read management reviews. That education, and a streak of perfectionism, have served him well. He realised early on that as India’s economy opened in the 1990s its firms would have to raise their standards, benchmark themselves against the very best, and if necessary buy competitors. His foreign takeovers included Corus, a giant British steel firm, and Jaguar Land Rover. The first has been a financial disaster, the second a triumph. But both showed that Indian firms—and those from other emerging economies—deserve their place at the top table of global business.

Indians would love to claim that this lesson has been thoroughly learnt. Names like Mittal and Infosys are known all round the world. But India remains a country with too many protected industries, from shopping to coal mining and newspapers. Mr Tata himself was not always as keen to open up at home as he was to venture abroad. But for the most part he was a firm advocate of globalisation.

The other lesson from Mr Tata has to do with integrity. His group has not entirely avoided scandals. It faced a rogue trader in the early 2000s, and did not completely escape the furore over the bent award of telecoms licences in 2008. No doubt somewhere today, in this firm with $100 billion of sales, funny business is taking place. Rivals grumble that Tata’s current respectability masks a past spent toadying up to politicians in the years before and after India’s independence in 1947. But the fact is that Mr Tata, in public, and by widespread repute in private too, has stood against corruption. His attitude towards India’s political class has been one of polite distance. He has long attacked what he calls “vested interests”—code for crony capitalism, in which firms make profits by buying favours from officials and politicians.

Looking in the mirror

Crony capitalism has seldom seemed more of a threat to India. Back in the 1990s, the country’s leading firms—technology companies as well as Tata Sons—went to extraordinary lengths to be squeaky-clean. Family firms, which still control about 40% of India’s stockmarket profits, professionalised their management and listed their shares. But over the past decade things have gone backwards. The new money has been made in “rent-seeking” sectors, such as mining and infrastructure, with a lot of government involvement and little foreign competition; some mouth-wateringly large corruption scandals have occurred there. Too many family firms have lost interest in improving governance. Some, unwilling to relinquish control by issuing shares, have piled on debt, and now that they are in trouble, are bullying state-run banks to “extend and pretend”—roll over their loans rather than write them down. Such firms thus become state-supported zombies.

The Indian public is fed up. Anti-corruption agencies are newly vigilant. Business has become a hall of mirrors in which fingers point everywhere. Suspicion is so pervasive that even clean officials are terrified to prod along vital projects by clean companies for fear of being accused of favouritism.

The problems in parts of the private sector have thus become a macroeconomic issue. Investment by private companies has slumped—the main reason why economic growth has slowed from 10% to about 5.5%.

It is easy to blame all this on corrupt politicians. But somebody is paying the bribes. By standing out against graft so publicly and consistently, Mr Tata was ahead of his time. The irony is that by doing so he was preparing the way for the end of businesses such as his own. As India’s economy modernises and becomes more open and transparent, the rationale may disappear for sprawling, hereditary conglomerates, which use the bonds of kin to deal with a shortage of trust, and pool their managers and capital because the outside markets for these resources do not work well.

To that extent, Mr Tata may come to be seen as both the last of one breed of feudal corporate leaders—and the first of another more open bunch. Anybody who cares about India’s future, especially its billion consumers, should hope that the transition picks up speed again.

source: The Economist